Antony Feltham-White first contacted Gray-Nicolls in 2006. The request – like many we receive – was asking for kit donations.

While we do our best to facilitate as many as we can from cricket clubs and charities, something about Antony’s request was different. At the time he was stationed in Basra with 19 Light Brigade. Antony is an Army chaplain and made similar requests to other cricket brands for equipment that would help with morale.

“Truth be told I asked every cricket supplier I could think of. You were the only ones who responded” Antony explains. “You sent me a whole bag of bats, wickets and balls. I was so thankful not only because cricket is a universal language - I taught many children French cricket - but it probably saved my life.”

As we gather on the mezzanine that houses the Gray-Nicolls museum of cricket bats and artefacts from the last two centuries in Robertsbridge, East Sussex, the Reverend pauses, almost choked by the moment. All this cricketing history, while hugely important for supporters of the game and us as a company, rather pales into insignificance with the recent history that the chaplain has lived through in Basra and other war-torn areas. He takes a moment to compose himself, like a batsman facing up to another delivery from a fast-bowler.

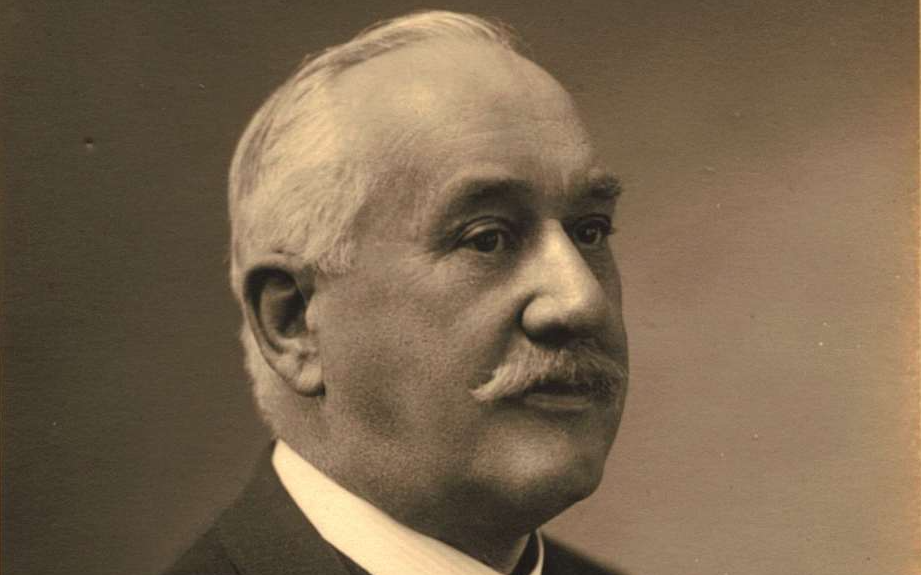

Antony with Gray-Nicolls CEO Richard Gray

He goes on to describe his experiences across Afghanistan and Iraq which put into perspective the stresses of everyday life, or our last rotten LBW decision.

“In Basra there was a successful sniper who was shooting my soldiers on patrols” he continues. “Under the Geneva convention I am not allowed to bear arms which made me feel more vulnerable on operations. Holding it like a firearm, the bat gave me a sense of protection - something to hold onto and occupy my hands, which reduced my anxiety in a stressful environment.”

The manner in which Feltham-White describes his experiences almost belies the seriousness of the situation. “Because my military training is more basic, I’m often not as aware how dangerous a situation may be” he says. “In Iraq I was regularly on the wrong end of rockets and mortars and had a few near misses. That was frightening as you could hear them momentarily before they hit, and if you could hear them they were coming close.

“I was in a pre-fab building that was hit by a rocket and my ears were ringing for weeks. I was also in an armoured vehicle in Afghanistan that was hit by an IED. The armour kept us safe but we sat and roasted in the thing for the best part of a day until we were recovered; the IED had taken a front wheel off.”

The cricket bat, rather than being a symbol of war, became one of peace, of fun, and good humour. Civilians would notice the bat and smile, approaching the Reverend to discuss his piece of willow. Those games of French cricket with Iraqi and Afghani children showed the power that sport has to overcome long-standing differences.

“I carried my Gray Nicolls bat on every patrol and it not only gave me great solace and comfort to hold it in my hand, it gave everyone a smile and I was often given the task of knocking back any grenades that came our way. Luckily none ever did” he continues.

“I spent a lot of time with local folk in what may be termed ‘religious friendship’. In both Iraq and Afghanistan, the people were intrigued to find a ‘holy-man’ amongst the military personnel. We organised Quran reading festivals for the locals which certainly helped reduce their level of suspicion and encourage some to come forward with information on the location of IEDs.”

Antony’s nature is gentle and softly spoken; it seems incongruous that this man would choose to spend his days risking his life when he could have another, more traditional role within the church.

“I never expected to be in the military, and it proves God has a sense of humour. Being a chaplain is closer to my vocation than I felt a parish priest was. I felt a bit like a petrol pump attendant who filled up people’s tanks on a Sunday and hoped they might make it back the following week. Now I’m riding in the car and even sometimes taking the wheel; the various journeys take me everywhere, and as an Army chaplain that has allowed me to take some light into some very dark places. It is a privilege to do this.”

A Lancashire boy through and through, the Reverend cites some Old Trafford legends as his cricketing idols. “I was particularly encouraged to meet Clive Lloyd when he visited my school; I’m a proud child of Manchester and Lancashire cricket. I’d also pick Wasim Akram and James Anderson as favourite Lancashire players and perhaps even Andrew Flintoff – you sort of have to add him as he is larger than life and wears his heart on his sleeve.”

As Feltham-White is taken on a tour of the Gray-Nicolls factory, conversation turns to the Afghanistan he left behind and how cricket has developed there over the past decade.

“Sport brings us together, it transcends language, culture and religion. Who does not love to hit a ball with a bat? Every child does, boy or girl. Gray-Nicolls sent me two bats to carry on operations. I left one in Afghanistan with a local young man with a passion for cricket the like I have not seen anywhere else. I suspect that bat has been played with every day for the last ten years. It was great to see the Afghanistan team playing well in 2019; I hope we continue to see them.”

Given recent events in the country, it is pertinent to ask the Reverend what his hopes are for Afghanistan going forwards. The horrific images of the Taliban takeover and horrified Afghans desperately trying to flee will live long in the memory.

“That is a big question. I believe we planted many seeds of peace, hope and love into the rich soil of Afghanistan, I know they will come to harvest at some time in the future. I fear there will be much pain yet sadly.

“Many thousands of years ago that area of the world was the crucible of the Zoroastrian religion, a monotheistic faith that simply said to defeat evil we must do three things: think positive thoughts, say kind words and do good deeds. Going forward we must not imagine the first two are enough. Afghanistan still needs us all to carry through all three in however we can.”

As we part, it is easy dismiss cricket as a mere folly when compared to what Feltham-White has experienced. Of course, it is. However, the power of our sport to positively impact lives all over the world is a something to be proud of. The Reverend’s experience is testament to that.